Remembering Srebrenica Thirty Years After the Genocide

By: Daniel Miller

7/13/25

“The men were looking at me, speechless. I had the feeling they had given up on their lives. Some of them grabbed my shoulder, asking: ‘Translator, what will happen to us?’ I answered, ‘They will allow women and children to be transported, and they will kill all the men.’ The men remained silent as I left the factory hall.”

— Hasan Nuhanović, genocide survivor and UN interpreter

The above quote is posted on one of several placards in the halls of an old battery factory that now serves as the genocide museum in Potočari, a small village located in the mountains of eastern Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH). In March 2022, I stayed two nights in Srebrenica, a town a few kilometers south of the museum, where tens of thousands of Muslim refugees were forced to flee from Bosnian Serb forces that eventually resulted in Europe’s deadliest conflict since the 1940s. The town remains paralyzed from those horrific events thirty years ago, and its dynamics don’t make much sense: there were plenty of cars that lined the streets, but there was hardly anyone walking on the sidewalks. Many of the cars had dust on the windshields, and so did the windows of several failed restaurants, something else that was difficult to find. I managed to find a place to eat that was kind of hidden, and I found another small one that only served burek, a popular meat- or cheese-filled Balkan pastry. Other than that, there wasn’t much else besides a small hardware store, a modernized school and police building, and a big grocery store without much variety. It’s as if the entire town is on life support.

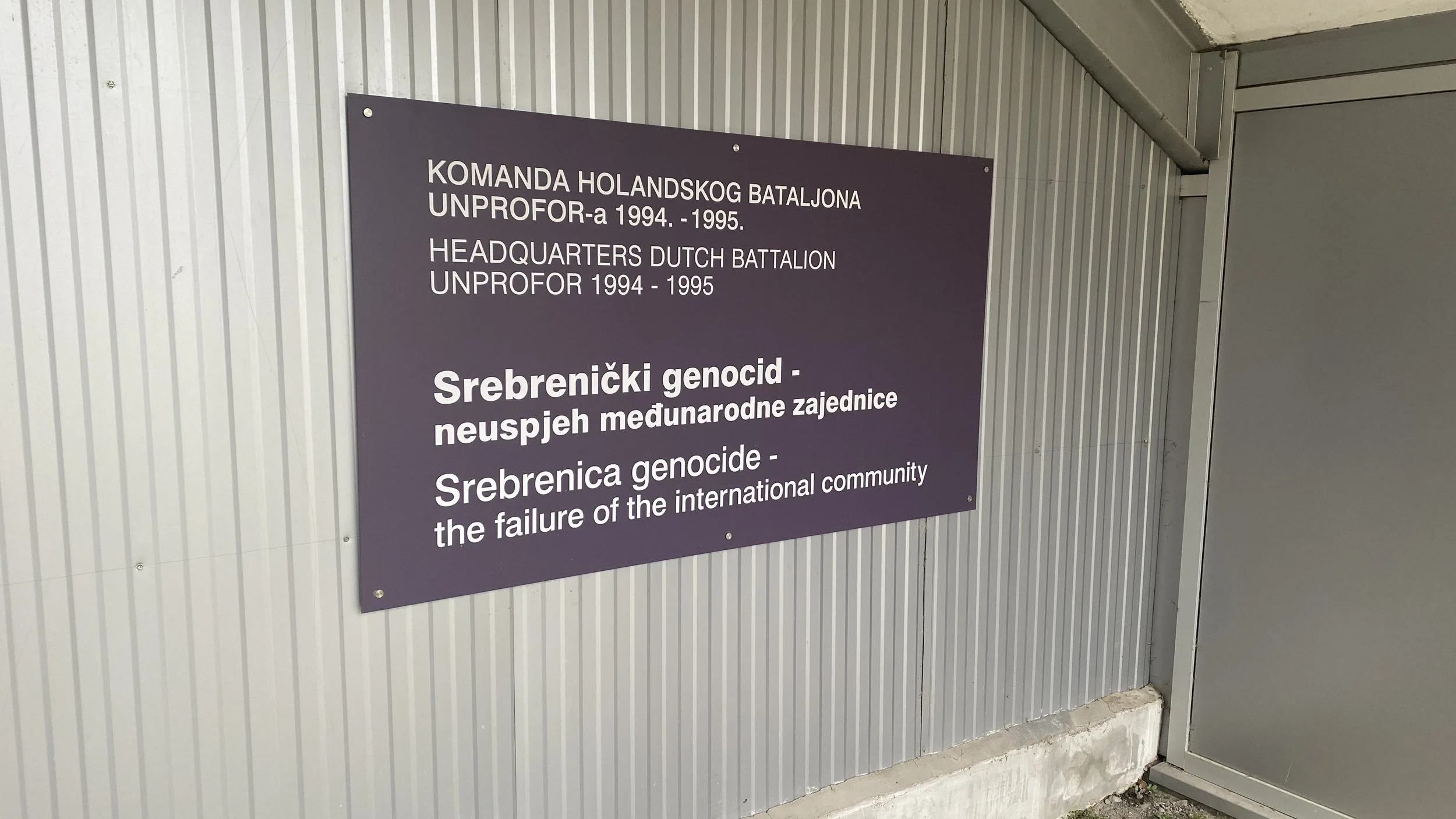

On the road to the museum, the same burned and war-torn houses and structures can be found, just like everywhere else around the country. The old UN headquarters sits on the east side. About 500 meters down the road, thousands of gravestones cover the hillside, with nearly all of them ending in the year 1995. The museum tells Hasan Nuhanović’s harrowing story of when he had to say a final goodbye as his family was separated and sent to die at the hands of Serbian nationalists. On July 11, 1995, the Bosnian Serb Army (VRS), led by General Ratko Mladić, began shelling the besieged village of Srebrenica, forcing nearly 25,000 refugees to flee five kilometers north to the compound in neighboring Potočari.

As part of an agreement brokered with the Bosnian government, the 2,000 poorly trained soldiers of the 28th Division of the Army of BiH were required to surrender their weapons to the UN. In exchange, the area was designated as one of four UN safe zones in eastern Bosnia, since much of the eastern and some northern territories were occupied by the VRS. The VRS called the region Republika Srpska, where many Serbian and Bosnian Serb nationalists to this day envision an ethnically pure, Orthodox Christian country.

The war began in response to Bosnia’s secession from Yugoslavia three years earlier, following an independence referendum that was passed with 99.7% of Croats and Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims) voting in favor of independence while Bosnian Serbs boycotted it. Representing roughly a third of the total ethnic population, Bosnian Serb leaders such as Radovan Karadzić refused to accept a Bosnia that was separate from Yugoslavia. The results were subsequently recognized by the UN, and the VRS would soon start its regional ethnic cleansing campaign and nearly four-year siege of the capital city, Sarajevo.

Dutch Lieutenant Colonel Thom Karremans, whose small battalion known as Dutchbat had just replaced Canadian peacekeepers as the next rotation to guard the safe zone, requested NATO airstrikes a day earlier against the advancing VRS positions early that morning, but was initially denied by the UN for submitting the wrong request forms. Over three hours later, twice the amount of time it takes to walk between the two towns, limited NATO airstrikes hit advancing VRS positions, which ceased after General Mladić threatened to execute several dozen Dutchbat peacekeepers who had been taken hostage days earlier. Srebrenica fell later that afternoon.

Only five thousand refugees – mostly consisting of women, children, and the elderly – were allowed into the compound by Dutchbat, despite Nuhanović pointing out that there was room for a few thousand more. “I could see fear and disbelief in the eyes of those who remained outside. There were whole families there. At one point, the mass of refugees pushed forward, but the Dutch joined hands in the cordon, and the refugees gave up after some time, not because they could not physically break through, but because they did not want to hurt the Dutch Blue Helmets…The space inside the compound was vast (some 120,000 square meters), and we all thought then, as we think now in retrospect, that thousands more refugees could have been admitted inside, and that is why the refugees came to Potocari in the first place.”

It was only a matter of time before the VRS began seizing Dutchbat weapons. Survivors say they witnessed shelling attacks and arbitrary murders by VRS forces as they moved towards Potočari. By this time, thousands had already fled or had just started fleeing over 100 kilometers north, as they risked being blown up in the dense forest by VRS-placed landmines, to the next UN safe zone at the city of Tuzla. With a third of the refugees dying by gunfire or explosives along the way, the journey would later be called The Death March of Srebrenica. Hasan Nuhanović was one of the survivors.

Mladič’s victim mentality and anger about NATO retaliation strikes that day and during the war were visible in a later propaganda video that was filmed that night, during a meeting with Karremans about safely transferring the refugees, at the Hotel Fontana in neighboring Bratunac. Karremans appeared visibly nervous throughout as Mladić pressured him into cooperating with the forced evacuations. The VRS then soon separated all males above 11 years of age from the rest of the women and children, who were mostly sent to Tuzla, while the rest of the 8,372 men were rounded up and summarily executed over the next few days. Thousands were forced into various warehouses and schools, where VRS soldiers would mow them down with gunfire and finish them off with grenades. Bulldozers ran through the night as the bodies were buried in mass graves – some still breathing – that would later be exhumed by the VRS in an attempt to cover up their crimes. Most of the bodies buried in Srebrenica are incomplete, with many graves only containing a few bones or fragments.

Survivors recall the blood-curdling screams coming from the forest throughout the following nights. Hasan’s testimony at The Hague years later helped expose the failure of Dutchbat and the UN to properly protect the refugees, and also exposed and validated the countless war crimes perpetrated by the VRS, paramilitary groups like the Skorpions, and even Bosnian Serb policemen. In 2007, he sued the Netherlands, claiming that the country bore responsibility for his family’s death because Dutchbat knew that they would be killed once expelled from the base. The Dutch Supreme Court ruled in his favor in 2013, and his testimony helped establish legal precedent regarding a state’s liability during peacekeeping missions. Ratko Mladić was captured by Serbian and Bosnian Serb authorities on May 26, 2011, in the village of Lazarevo, Serbia. He was sentenced in 2017 and is currently serving life in prison in The Hague for genocide and crimes against humanity.

During a 1993 interview with Independent Television News (ITN), Holocaust survivor and US Congressman Tom Lantos, who served on the Foreign Relations Committee, was highly critical of the European Community and President George H.W. Bush, Sr., for failing to take action as soon as it was necessary:

“It’s obvious that public opinion is way ahead of our leadership. Mr. Bush and his administration have to be dragged kicking and screaming into taking some action…it is self-evident that without united military intervention under United Nations auspices, led by the Europeans but participated in by the United States, the slaughter at Sarajevo and throughout Bosnia will continue. And it’s unconscionable for the civilized world to allow this to happen.”

This prescient statement encapsulates the typical tepid approach the collective West has always taken when it comes to addressing conflicts in its own backyard, especially since the end of the Cold War. It’s as if the leaders truly believe that the mass murdering invaders will suddenly realize that what they are doing is wrong, and will put down their weapons and apologize. For 26 years, they have been afraid of angering a thug like Vladimir Putin and scared of the anti-Western propaganda that will always exist no matter what happens, and is a major factor as to why democracy has been backsliding around the globe. Sarajevo was surrounded and shelled every day for almost four years, and the killings and concentration camps only stopped once the West interfered. This same attitude has been particularly salient in regards to Georgia and Ukraine, which is the main reason why both countries are currently facing existential crises of their own.

I’ve come across plenty of so-called peaceniks who hold an ostensibly common-sense position that war is bad and one country shouldn’t interfere in the affairs of others, even if those two are at war. But it’s not common sense to watch an innocent person being beaten by a thief, and anybody with a shred of morality and dignity would do their best to prevent further harm, no matter what. A person seeking shelter during a bombing campaign doesn’t care who comes to save them; they just want to be saved. Inaction only emboldens bullies even more, and prioritizing political caution over saving human lives is deeply immoral. What happened in Rwanda is a classic case of non-intervention, and Kosovo is a great example of cutting the head off the snake that promised to bite once it got close enough. It’s never wrong to criticize military actions that resulted in civilian casualties, but it’s intellectually lazy to disregard any contemplation about the lives and destruction that were prevented. There are no perfect solutions to reverse the conditions created by an aggressive invader, but somehow, the liberating forces are the ones who come under the most amount of scrutiny.

The VRS violated every single item of the NATO charter that binds the member states, and at the time, BiH was a member of NATO’s Partnership for Peace (PfP) program. Regardless of that fact, I share the same views as every Bosnian who has been affected by the war, which is that NATO was right to intervene, and they should have done so years earlier.